In this short post, I describe a simple new way to abuse an access token that is scoped to the Azure Resource Manager(ARM) APIs. This abuse technique is very easy, but can be an effective way to escalate privileges or move laterally from an ARM access token.

TLDR;

- The Azure Resource Manager (ARM) REST APIs for the Microsoft.Web resource provider contain several undocumented, global endpoints that do not required authorization via an RBAC role

- Abuse of these endpoints with a compromised guest user can lead to compromise of app services and functions, as well as theft of cleartext PAT tokens for Github

- These endpoints contain global configurations for a user, which means that tokens for a guest user can be abused for cross-tenant abuse

- Microsoft considers this to be expected behavior

Background - ARM Tokens and Authorization

The ARM REST API was the target of this research. To make the rest of the article accessible, let's quickly explain the basics of the ARM API and authorization to the API.

ARM is the only API that can be used to perform administrative operations on Azure resources. In order to use it, an access token must be presented to the API, and the identity referenced in that access token must be authorized to perform an action at some scope within the tenant.

To authorize an identity to use the ARM APIs, an admin must assign the identity an Azure RBAC role at some scope in the tenant, such as a management group or subscription. The RBAC role will define what operations that identity can perform on resources that are deployed at or below that scope. For example, the website contributor RBAC role allows an identity to perform administrative operations such as modification of source code and re-deployment on an app service or function.

This role assignment requirement is the primary security mechanism of ARM. Any user in a tenant can request an ARM access token, but cannot generally use that token unless they are assigned some RBAC role.

The RBAC role assignment security mechanism extends to the tenant boundary as you would expect - a guest user needs a role assignment at any relevant scope to be able to call the ARM APIs, which means that new assignments are required per-tenant.

So what happens when there are undocumented ARM APIs that deviate from this approach? If these APIs are sensitive, how can they be abused, and in what scenarios? This is the topic of this blog post, and we will visit scenarios where this is relevant later.

Understanding the Tenant Boundary

Most folks that work with Entra ID are familiar with the idea of a "Guest User", or "B2B User". A guest user is essentially a user from one Entra/M365 tenant that has been invited into another tenant, and can be given role assignments to access resources in that tenant, such as SharePoint sites or OneDrive files.

Generally, a token that is issued for a user can only be used to influence resources that belong to the tenant that the token was issued for. So if a user token is stolen, that token cannot be used in all tenants the user belongs to, and can only be used in the tenant it was originally issued. This is a fundamental security boundary of Entra ID - If a user is a guest user within other tenants, those guest users are treated as separate user accounts in each tenant, with their own roles and their own settings.

The Issue - Global ARM APIs

During this research, it was particularly surprising to learn that there are a few undocumented ARM API endpoints that contain global configurations for a user account. Calling these API as a guest user returns the same information as calling the API as that user in their home tenant, which seemingly breaks the tenant boundary.

This isnt necessarily a security issue - for example, the https://management.azure.com/tenants API is a "global" ARM endpoint, and simply tells the user what tenants their user exists in. This has no real security implication, and is a convenience feature that is used for the "switch tenant" feature in the portal. (As an aside, it is also quite useful when evaluating what access you might have with a stolen token).

However, the APIs identified in this post are not as benign as the /tenants API - they allow a user to both read and write secrets for their global user account, which ultimately can lead to cross-tenant abuse of a guest user by anyone that can get a token for that user.

These endpoints are:

- https://management.azure.com/providers/Microsoft.Web/publishingUsers/web?api-version=2024-11-01

- https://management.azure.com/providers/Microsoft.Web/sourcecontrols?api-version=2024-11-01

Microsoft.Web Deployment Options

The endpoints above are related to the CI/CD features in App Services and Functions and a user's Deployment Credentials. Specifically, the sourecontrols endpoint is used when provisioning continuous deployment for App Services, which rebuilds and deploys any change to a specific source control branch. This API is used to update or retrieve a high-permission PAT token for a user.

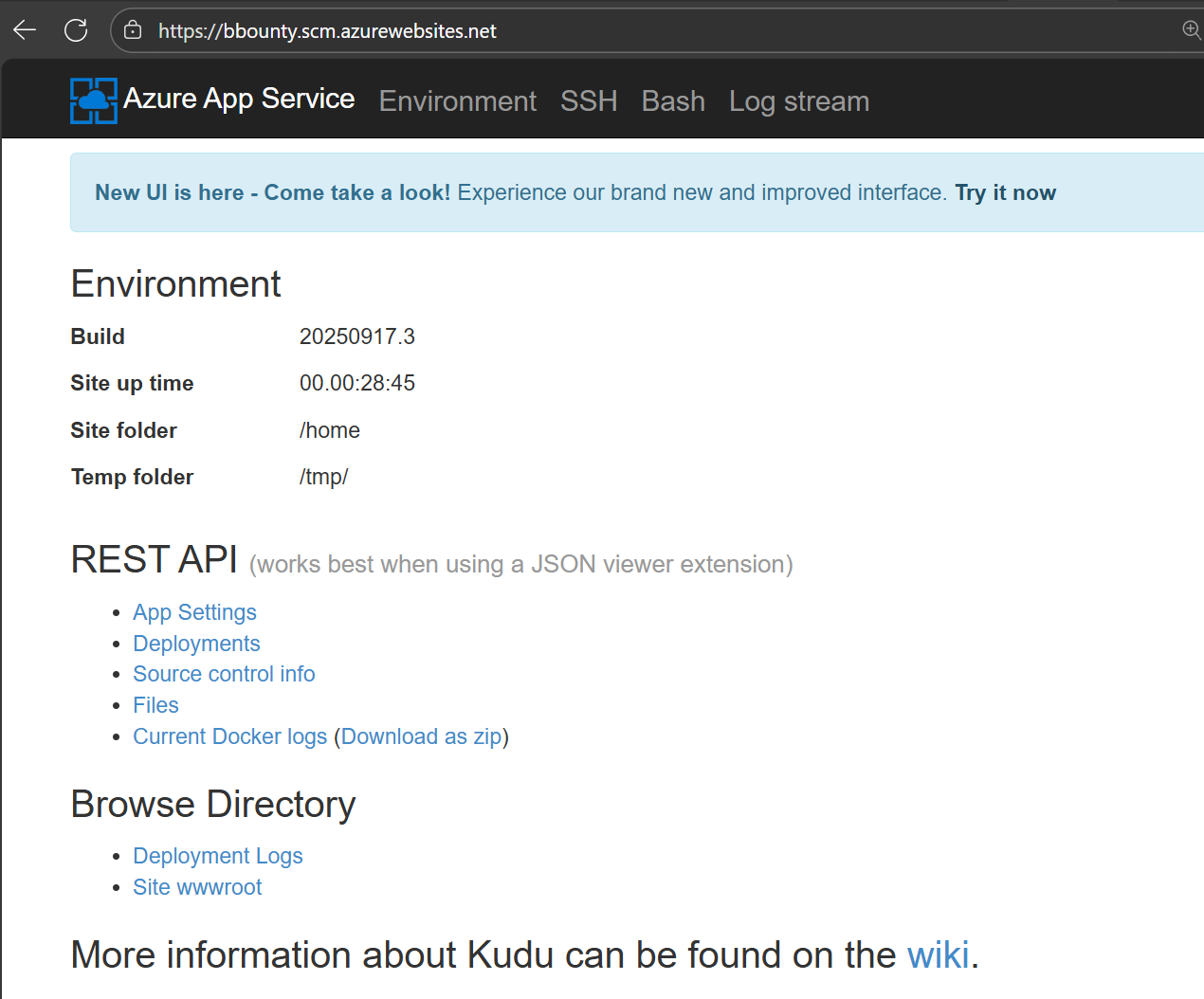

On the other hand, the publishingUsers/web endpoint is used for managing user-level deployment credentials. User-level deployment credentials are a simple password that all users can set, which can be used to log in to the administrative interface (Kudu) of an app service/function, or call the kudu APIs to perform deployments.

Since both of these endpoints are not authorized, lets take a look at when and how we can abuse them.

1) User Deployment Password Abuse

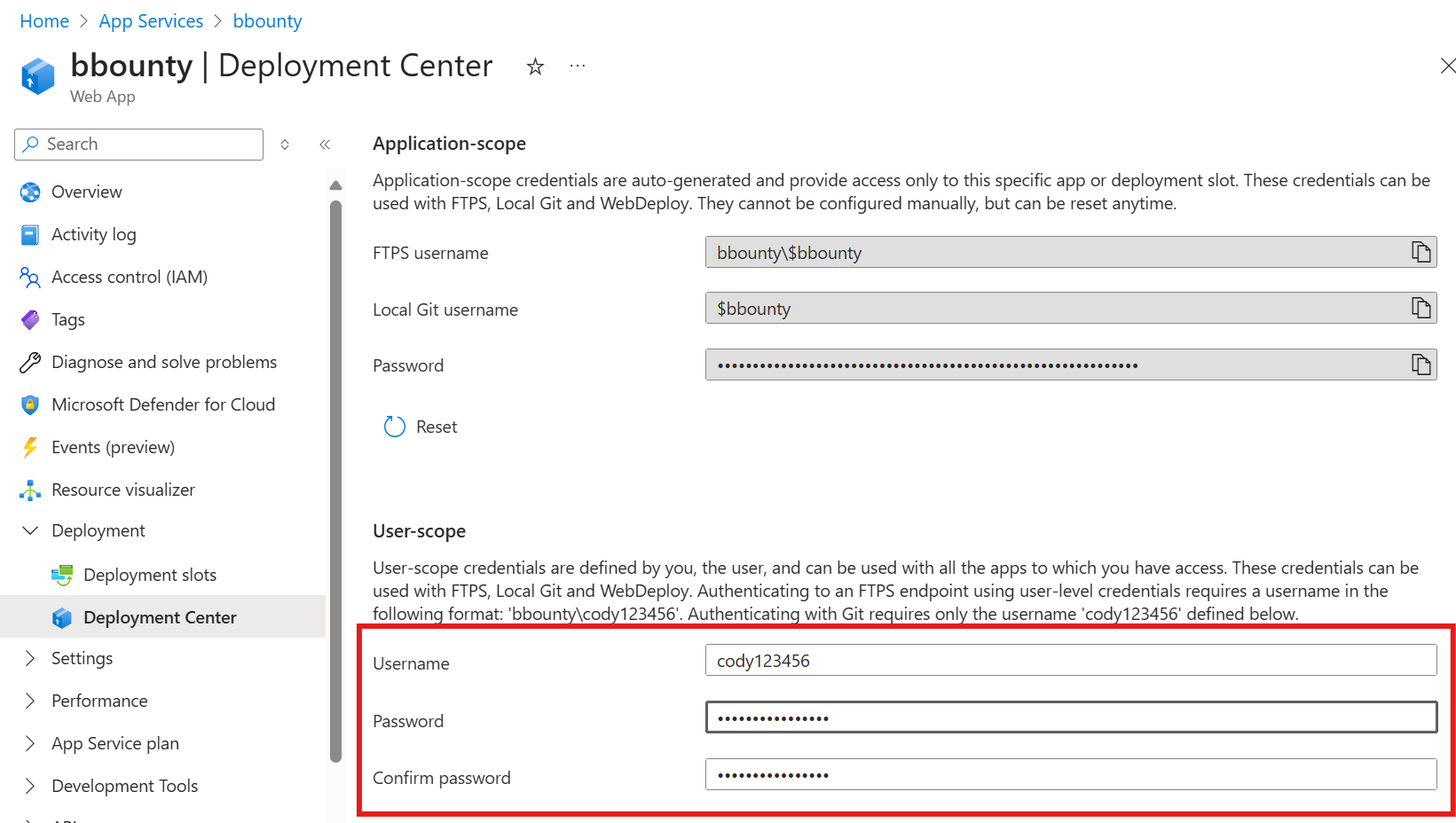

The first API is used to set a User Deployment password in the portal:

When a new password is set, it is set globally for that user, in any tenant that user exists in. Since the endpoint does not require authorization via an RBAC role, a compromised ARM token for a guest user can always be used to set a global deployment password.

So what does this mean? As described in the background, these deployment passwords can be used to interact with the administrative interface of an App Service, as long as the user is at least a Website Contributor. With this password, you can perform at least the following tasks as a website contributor:

- Dump memory

- Change source code

- Re-deploy

- Upload and download files

- Execute code

So why does it matter if the user is required to have an RBAC role? Well, in many scenarios, a guest user may have an RBAC role assignment in one tenant for an App Service or Function, but have no RBAC role assignment in another. A classic example would be an MSP scenario. In this setup, compromise of the user in any tenant would lead to cross-tenant admin access to app services.

To abuse this endpoint, lets assume that you have already stolen an ARM token. Calling the API is as simple as the following command:

az rest --method get --uri "https://management.azure.com/providers/Microsoft.Web/publishingUsers/web?api-version=2024-11-01"

Output:

{

"id": null,

"name": "web",

"properties": {

"isDeleted": false,

"metadata": null,

"name": null,

"publishingPassword": null,

"publishingPasswordHash": null,

"publishingPasswordHashSalt": null,

"publishingUserName": "cody123456",

"scmUri": null

},

"type": "Microsoft.Web/publishingUsers/web"

}

Now, note that the PublishingPassword is null. This is always the case - the API does not return the plaintext publishing password. However, setting it is as simple as using the PUT method and setting the json value:

az rest --method put --uri "https://management.azure.com/providers/Microsoft.Web/publishingUsers/web?api-version=2024-11-01" --body '{"properties": {"publishingPasword": "TestPassword123#"}}'

output

{

"id": null,

"name": "web",

"properties": {

"isDeleted": false,

"metadata": null,

"name": null,

"publishingPassword": null,

"publishingPasswordHash": null,

"publishingPasswordHashSalt": null,

"publishingUserName": null,

"scmUri": null

},

"type": "Microsoft.Web/publishingUsers/web"

}

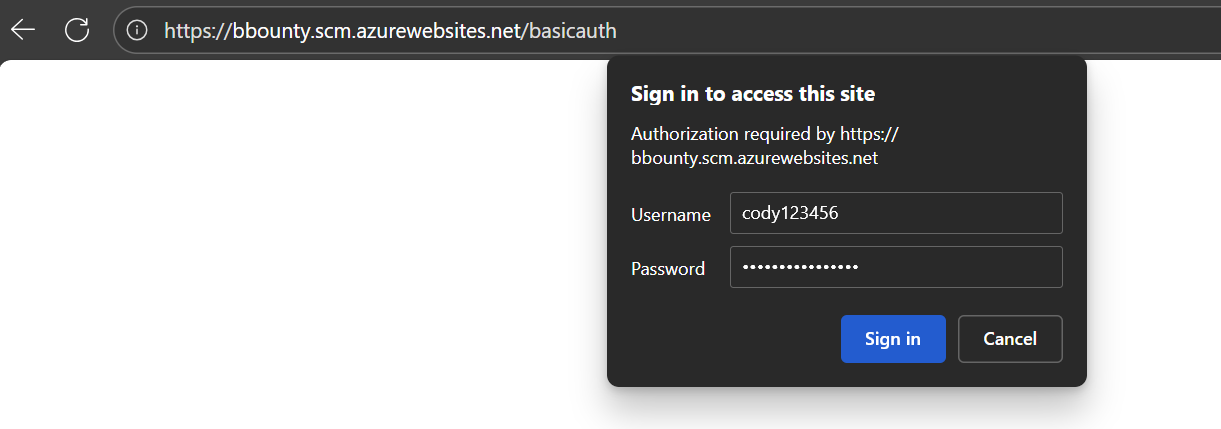

By setting the publishing password in any tenant, you can now take over App Services the user has permissions to modify. Note that there is one restriction: basic auth publishing credentials need to be enabled on the App Service for SCM. There are several ways to do this, but the simplest would be to login to the App Service Kudu console with the new credentials:

2) Continuous Deployment Configuration Abuse

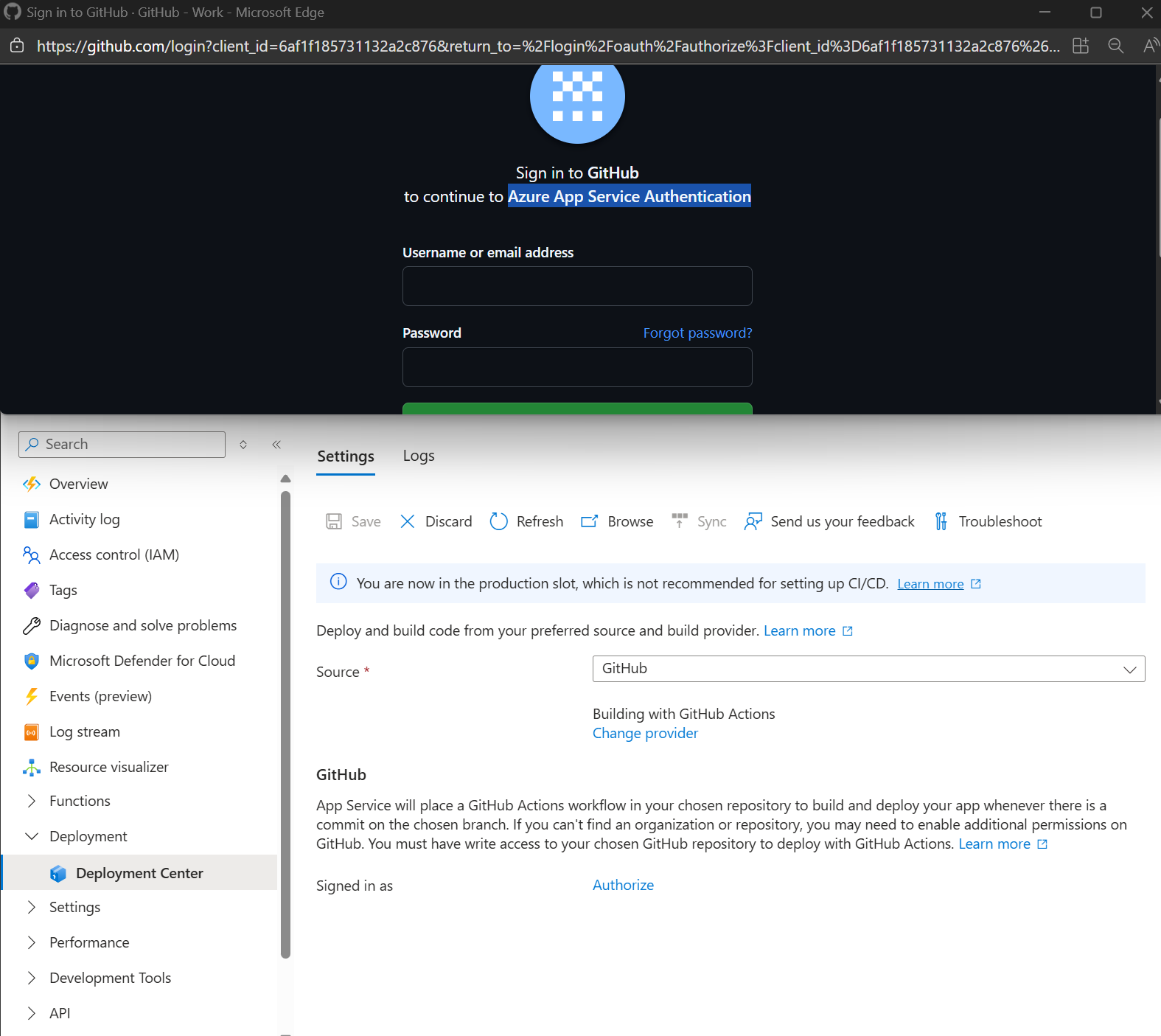

The second API is used for configuring continuous deployment to an app service via some source code repository.

The configuration requires a personal access token(PAT) to be sent to the API, which the API stores in plaintext. To retrieve the plaintext PAT token, simply call the same endpoint with a GET request. After setting up Github for continuous deployment in the deployment center, the portal will store a PAT token with the second API Endpoint above.

So what privileges does the PAT token have?

By default, when this setting is configured in the portal for Github, the PAT token that is configured includes priviled access to all repos that the Github user has access to. This is convenient for users, since they only need to configure this once. However, that means that compromising a user's ARM token in any tenant would allow an attacker to also gain full admin access to any repository that the user has access to in Github. Generally this would lead to takeover of the product via CI/CD attacks, and likely lateral movement to other projects the user has access to.

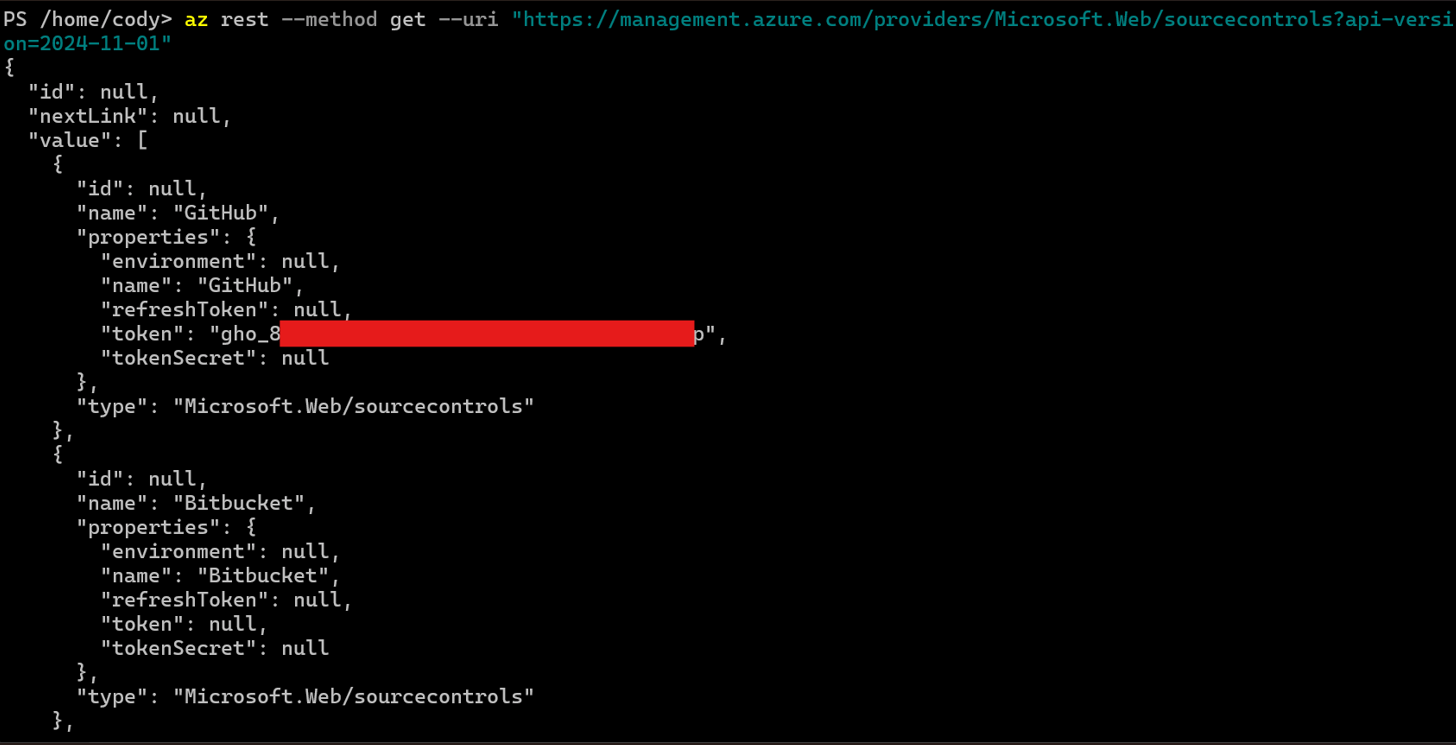

Abuse is similarly simple - the following command will return the plaintext token, which can then be used to call Github APIs:

az rest --method get --uri "https://management.azure.com/providers/Microsoft.Web/sourcecontrols?api-version=2024-11-01"

What are the abuse scenarios?

There are a few concrete scenarios where these APIs are useful for as an attacker, but any scenario would be largely dependent on whether the compromised user has access to any app services or functions, or has set up a user deployment credential. These scenarios are therefor mostly relevant for targeting developers and administrators.

-

Simple lateral movement to GitHub - Since you can receive a plaintext PAT token from the sourcecontrols API, it is trivial to call that endpoint, steal the PAT token, and move laterally to a compromised developer's Github account. This can lead to a large new attack surface for an attacker

-

Lateral movement between tenants - The User Site Credentials are a great way to move laterally from a guest user to other tenants. If you can identify an app service in another tenant which the guest user has contributor access to, the user site credential can be used to gain admin access to the app service without needing to first compromise that user's account in the other tenant. This is limited in scope, but occasionally an over privileged managed identity on an app service can be a good pivoting point into a new tenant.

-

Phishing guest users to bypass controls - In some cases, it may be difficult to bypass conditional access policies even after a successful phish. However, if the user exists as a guest in another tenant with more lax policies, it could be possible to phish guest users in the second tenant, and use these endpoints to try to pivot back to the target tenant. For example, an attacker could reset a user's deployment credentials, then access the Kudu interface of a web app in another tenant without worrying about conditional access

What was Microsoft's Response?

Microsoft was offered the chance to review and comment on this report. In response to this report, Microsoft states the following:

“Our engineering team has carefully reviewed your report and confirmed that they understand and acknowledge the potential attack vector. While this attack vector requires a successful phishing attempt on the victim, we have initiated efforts to address the identified gap, including collecting relevant telemetry to inform their approach to further protect customers. This data will help our teams determine whether to restrict API access to trusted AAD apps or to move toward a per-tenant approach. This is a continuous and evolving effort, and based on current analysis, we expect the full remediation to be completed over the next several months. In an effort to minimize the risk of introducing breaking changes while implementing major updates, we are proceeding with caution. We recommend customers continue to carefully review any links sent via email or text from unknown sources, nor to consent to join an EntraID organization without first verifying its identity.”

Timeline for reporting:

- June 11: Initial Report

- August 23: Microsoft confirms issue at moderate severity, but that they will not track the MSRC case

- August-September: Some discussion on severity and impact

- November 11: Report shared with Microsoft

- December 08: Published blog post.